LR Schedulers, Adaptive Optimizers

Contents

LR Schedulers, Adaptive Optimizers¶

A long long time ago, almost all neural networks were trained using a fixed learning rate and the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer.

Then the whole deep learning revolution thing happened, leading to a whirlwind of new techniques and ideas. In the area of model optimization, the two most influential of these new ideas have been learning rate schedulers and adaptive optimizers.

In this chapter, we will discuss the history of learning rate schedulers and optimizers, leading up to the two techniques best-known among practitioners today: OneCycleLR and the Adam optimizer. We will discuss the relative merits of these two techniques.

TLDR: you can stick to Adam (or one of its derivatives) during the development stage of the project, but you should try additionally incorporating OneCycleLR into your model as well eventually.

ReduceLROnPlateau, the first LR scheduler¶

All optimizers have a learning rate hyperparameter, which is one of the most important hyperparameters affecting model performance.

In the simplest case, the learning rate is kept fixed. However, it was discovered relatively early on that choosing a large initial learning rate then shrinking it over time leads to better converged, more performant models. This is known as learning rate annealing (or decay).

In the early stages of model training, the model is still making large steps towards the gradient space, and a large learning rate helps it find the coarse values it needs more quickly.

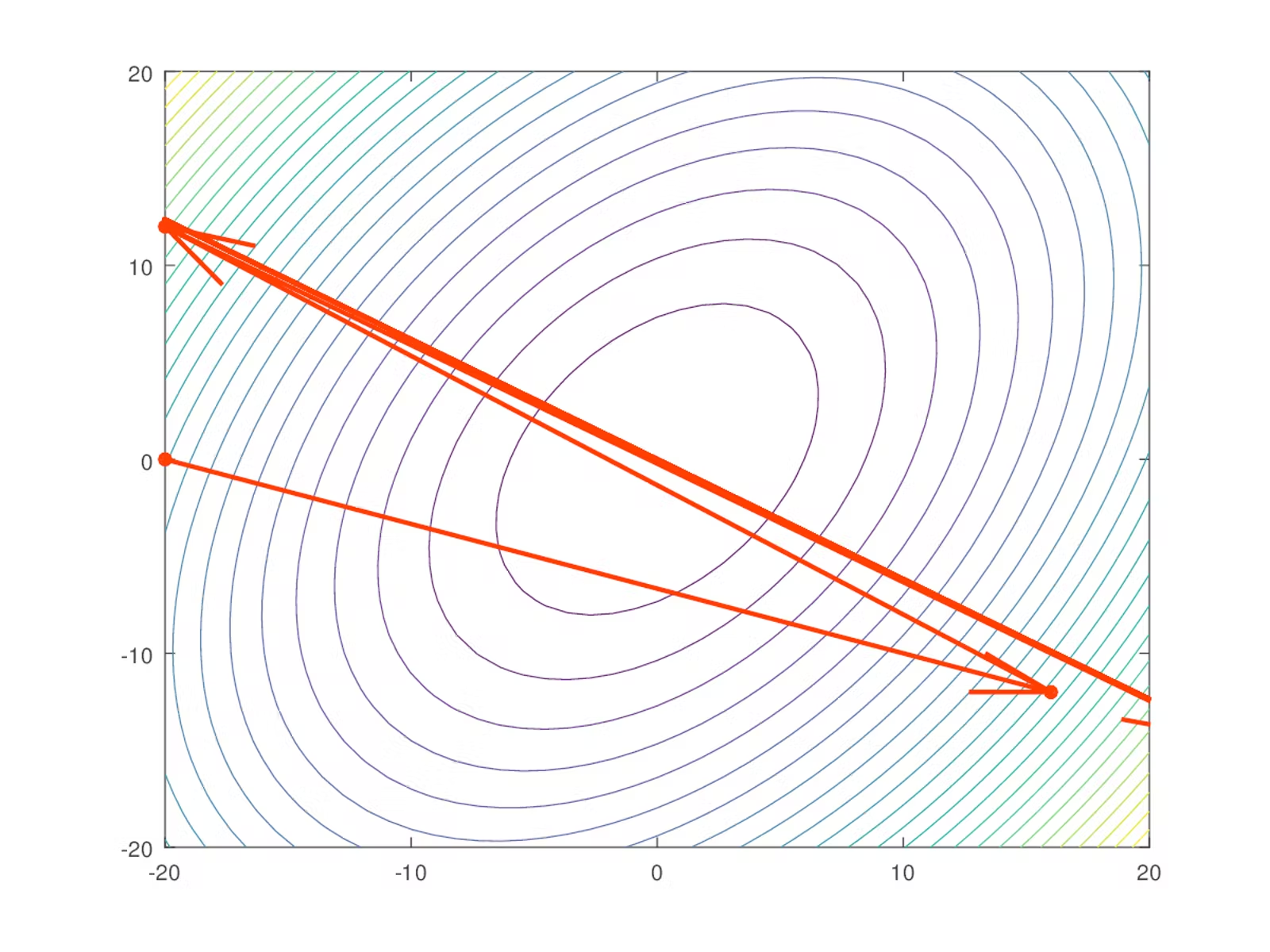

In the late stages of model training, the opposite is true. The model has approximately the right gradients already; it just needs a little extra push to find the last few percentage points of performance. A large gradient is no longer appropriate because it will “overshoot” the point of optimality. Instead of converging on the global cost minima, the model will bounce around it:

This observation led to the popularization of the first well-known learning rate scheduler, ReduceLROnPlateau (torch.optim.lr_scheduler.ReduceLROnPlateau in PyTorch). ReduceLROnPlateau takes a step_size, a patience, and a cooldown as input. After completing each batch of training, the model checks whether or not model performance has improved. If model performance hasn’t improved in patience batches, the learning rate is reduced (typically by a factor of 10). After a cooldown period, this process is repeated again, until the final batch of training completes.

This technique has squeezed out an extra percentage point or two of performance in pretty much every context it’s been tried in. As a result, some combination of EarlyStopping, ReduceLROnPlateau, and SGD was the state of the art until 2015.

Adaptive optimizers¶

2015 saw the release of Adam: A Method For Stochastic Optimization. This paper introduced Adam (torch.optim.Adam in PyTorch), the first so-called adaptive optimizer to gain widespread traction.

Adaptive optimizers eschew the use of a separate learning rate scheduler, instead embedding learning rate optimization directly into the optimizer itself. Adam actually goes one step further, managing the learning rates on a per-weight basis. In other words, it gives every free variable in the model its own learning rate. The value Adam actually assigns to this learning rate is an implementation detail of the optimizer itself, and not something you can manipulate directly.

Adam has two compelling advantages over ReduceLROnPlateau.

One, model performance. It’s a better optimizer, full stop. Simply put, it trains higher-performance models.

Two, Adam is almost parameter-free. Adam does have a learning rate hyperparameter, but the adaptive nature of the algorithm makes it quite robust—unless the default learning rate is off by an order of magnitude, changing it doesn’t affect performance much.

Adam is not the first adaptive optimizer—that honor goes to Adagrad, published in 2011—but it was the first one robust enough and fast enough for general-purpose usage. Upon its release, Adam immediately overtook SGD plus ReduceLROnPlateau as the state of the art in most applications. We’ve seen improved variants (like Adamw) since then, but these have yet to displace vanilla Adam in general-purpose usage.

Cosine annealed warm restart¶

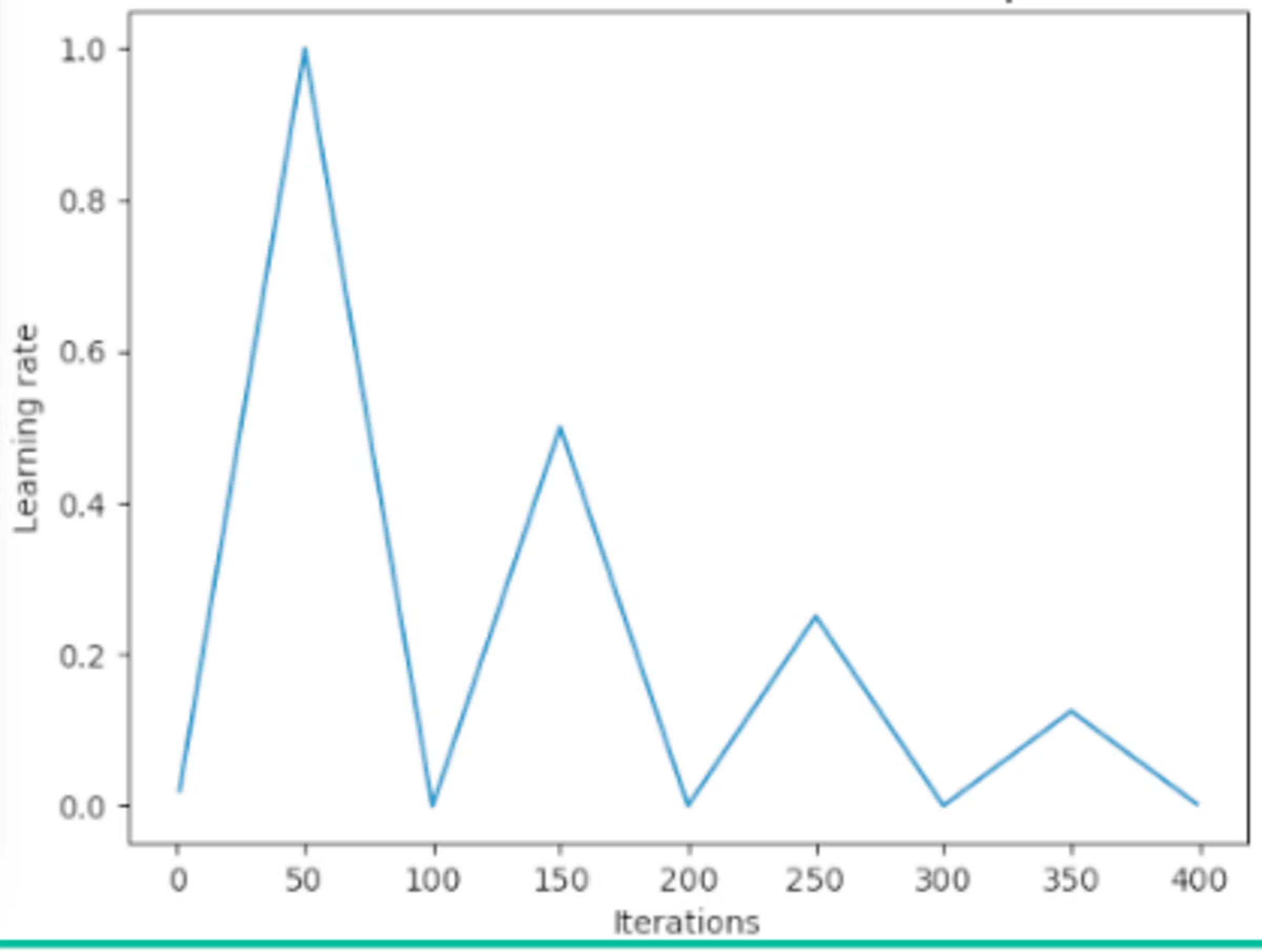

The next big step forward in this space was arguably the 2017 paper SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts popularized the idea of warm restarts. A learning rate scheduler that incorporates warm restarts occasionally re-raises the learning rate. A simple linear example showing how this is done:

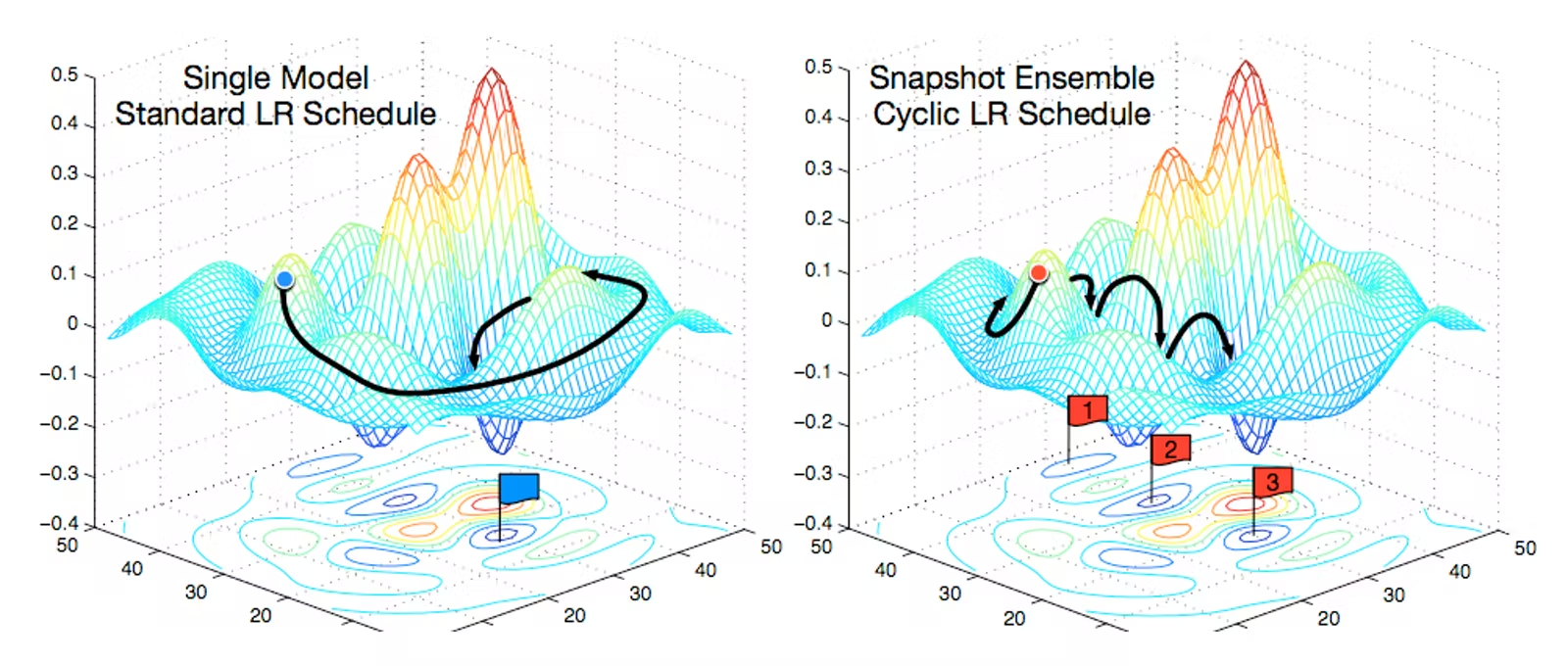

Warm restarts usually actually cause the model to diverge. This is done on purpose. It turns out that adding some controlled divergence allows the model to work around local minima in the task’s cost surface, allowing it to find an even better global minima instead. This is akin to finding a valley, then climbing a nearby hill, and discovering an even deeper valley one region over. Here’s a visual summary:

Both of these learners converge to the same global minima. However, on the left, the learner trundles slowly along a low-gradient path. On the right, the learner falls into a sequence of local minima (valleys), then uses warm restarts to climb over them (hills). In the process it finds the same global minima faster, because the path it follows has a much higher gradient overall.

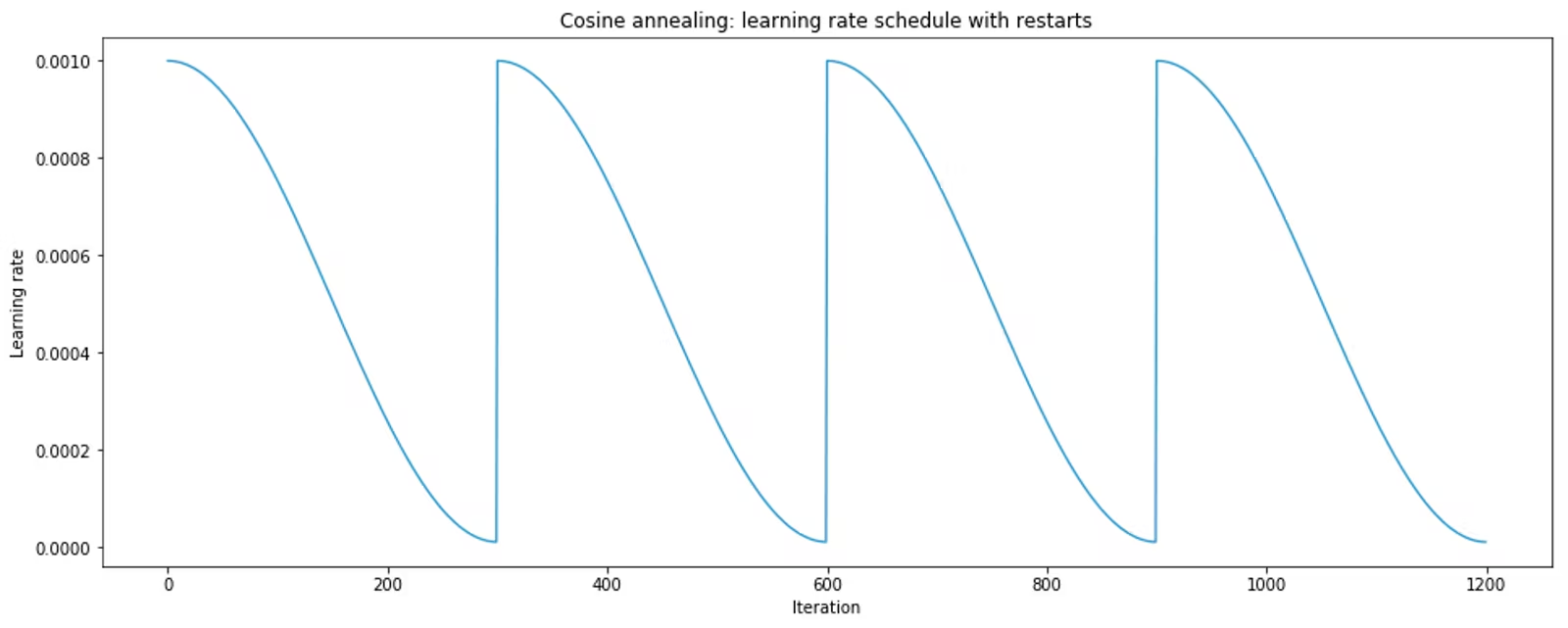

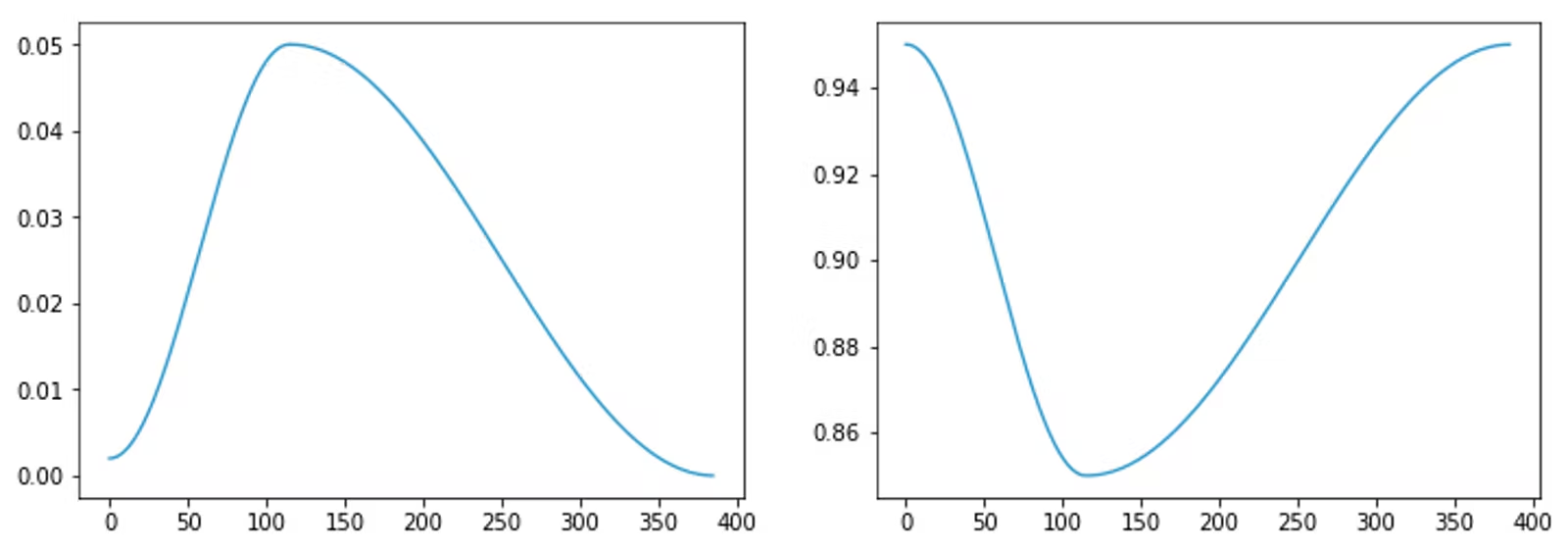

fast.ai popularized a learning rate scheduler that uses both warm restarts and cosine annealing. This scheduler has the following shape:

Cosine annealing has better convergence behavior than linear annealing, for reasons that are not entirely understood.

This learning rate scheduler was the default one used by the fastai framework for a couple of years. It was first made available in PyTorch (as torch.optim.lr_scheduler.CosineAnnealingLR) in version 0.3.1, released in February 2018 (release notes, GH PR).

One-cycle learning rate schedulers¶

fastai no longer recommends cosine annealing because it is no longer the most performant general-purpose learning rate scheduler. These days, that honor belongs to the one-cycle learning rate scheduler.

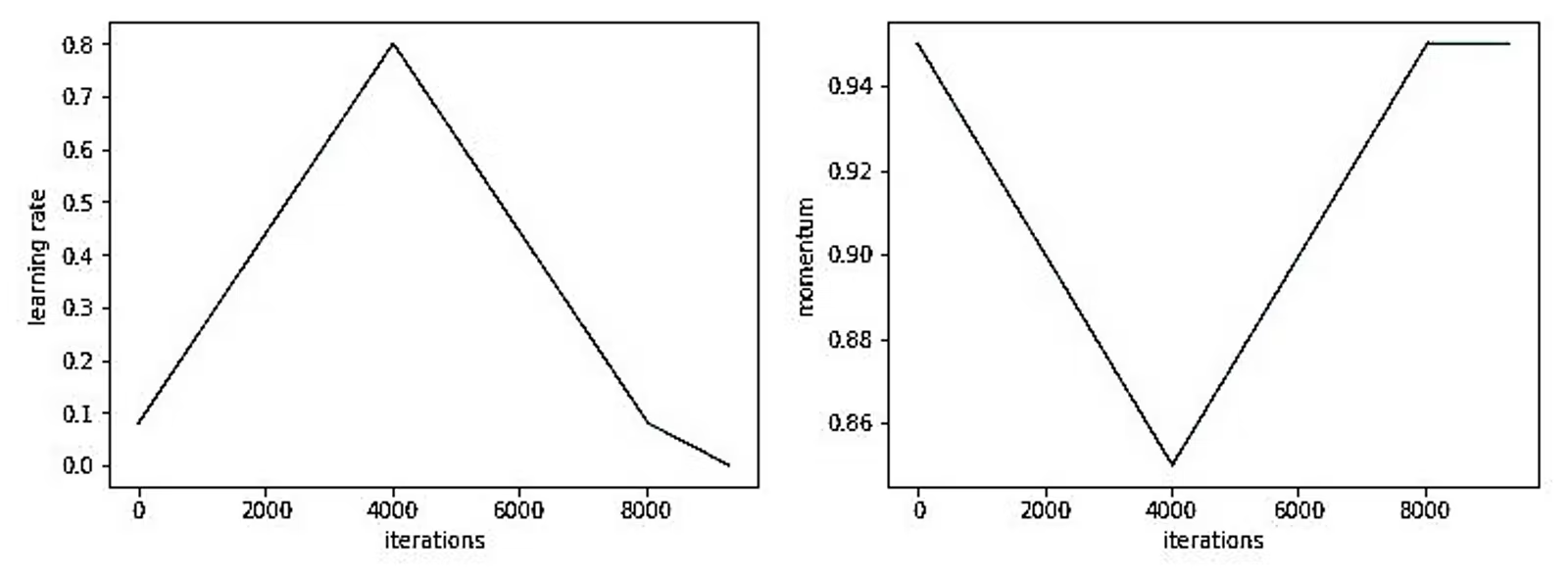

The one-cycle learning rate scheduler was introduced in the 2017 paper Super-Convergence: Very Fast Training of Neural Networks Using Large Learning Rates. The paper uses the following learning rate policy (which is applied over both learning rate and momentum):

Optimally, learning rate and momentum should be set to a value which just causes the network to begin to diverge at its peak. The remainder of the training regimen consists of warm-up, cool-down, and fine-tuning periods. Note that, during the fine-tuning period, the learning rate drops to 1/10th of its initial value.

Momentum is counterproductive when the learning rate is very high, which is why momentum is annealed in the opposite of the way in which the learning rate is annealed in the optimizer.

The one-cycle learning rate scheduler uses more or less the same mechanism that the cosine annealed warm restarts learning rate scheduler uses, just in a different form factor.

In their implementation, fastai tweaks this a little bit, again switching from linear to cosine annealing:

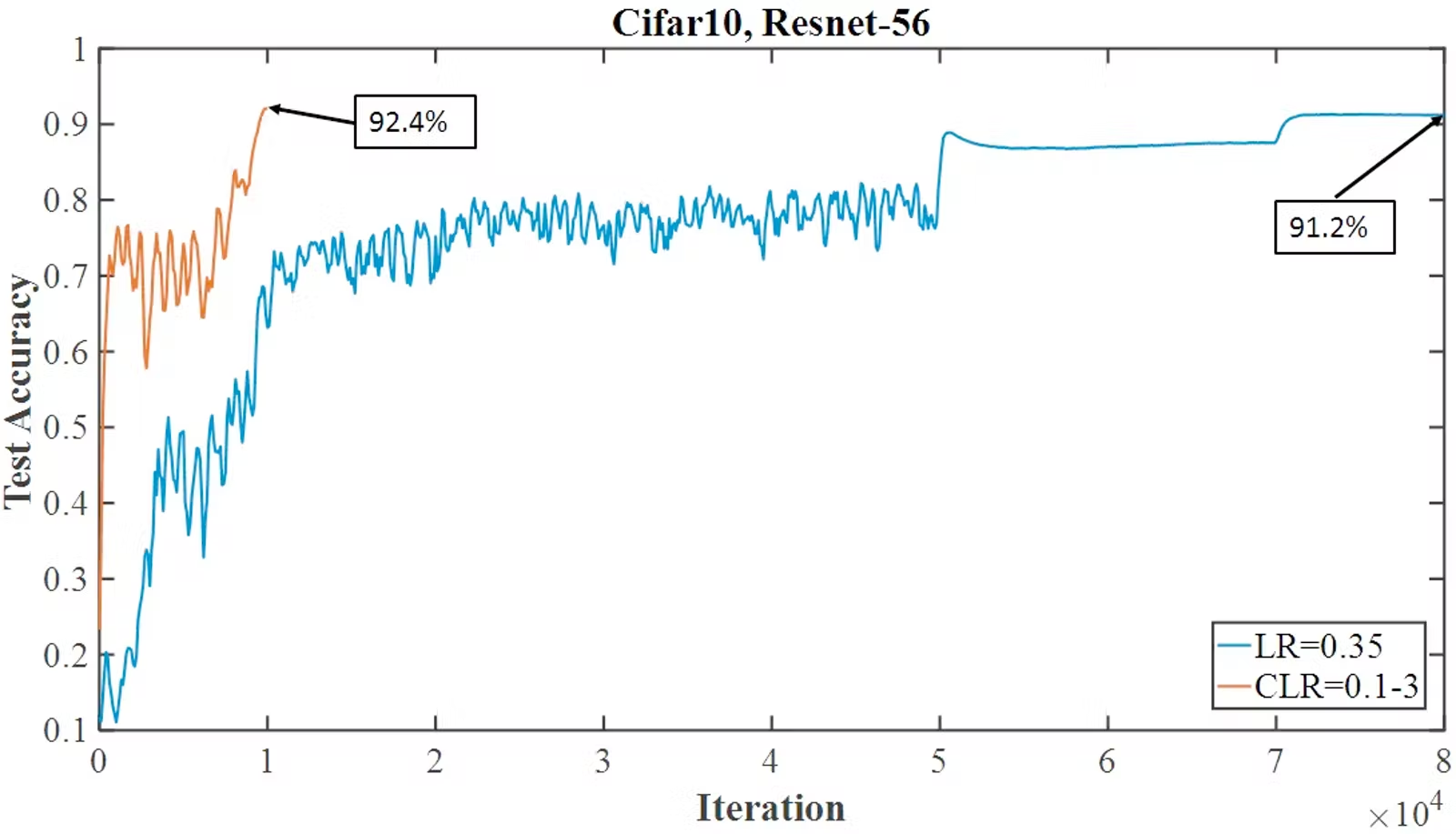

fastai recommendeded OneCycleLR plus vanilla SGD over Adam because, subject to some tuning (getting the maximum learning rate correct is particularly important), it trained models with roughly equal or marginally worse performance in a fraction of the time. This is due to a phenomenon that Leslie Smith, the once-cycle paper author, terms superconvergence. For example, the paper shows the following behavior on CIFAR10:

Though you shouldn’t count on results this compelling in practice, superconvergence has indeed been demonstrated on a broad range of datasets and problem domains.

The one-cycle learning rate scheduler was implemented in PyTorch in August 2019 (as torch.optim.lr_scheduler.OneCycleLR; here’s the GH PR).

The view from today¶

The first version of the fastai course to teach OneCycleLR did so pairing OneCycleLR with vanilla SGD (as it was presented and used in the paper). However, the current version of the course now uses Adam and OneCycleLR (specifically, Adamw) as its default.

This choice, and change, is explained at length in their blog post AdamW and Super-convergence is now the fastest way to train neural nets. The TLDR is that it wasn’t immediately clear that Adam performance was what it was made out to be in the academic literature of the time, and so the decision was made to cut it from the curriculum until further experimentation proved otherwise.

Even so, the “naked” Adam optimizer is predominant amongst practitioners today. You can see this for yourself by browsing recent starter kernels for Kaggle competitions, like this one, where you’ll see that the use of Adam predominates. Because Adam is pretty much parameter-free, it’s much more robust to model changes than OneCycleLR is. This makes it much easier to develop with, as it’s one fewer set of hyperparameters that you have to optimize.

However, once you’re in the later optimization stage of a medium-sized model training project, experimenting with moving off of Adam and onto OneCycleLR is well worth doing. Just imagine how much easier the lives of your data engineers will be if your model can achieve 98% of the performance in 25% of the time!

Hyperconvergence is an extremely attractive property to have, if you can spend the time required to tune it.