JIT

Contents

JIT¶

PyTorch JIT (torch.jit) is a nifty feature of the PyTorch library, which holds the secret to implementing performant custom module code.

If you’ve ever implemented a SOTA or near-SOTA neural network model, you’re very likely building and testing layer architectures from recent research that hasn’t yet landed in PyTorch core. Because these implementations have not been optimized by the PyTorch team, they are universally slower than their standard library equivalents.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. In this blog post, we’ll provide an overview of torch.jit: what it is, and at a high level, how it works. We’ll then look at some code samples that show how easy it is to use this API in practice, and some benchmarks showing how.

TLDR: torch.jit can be used to enable 2x-3x speedups on custom module code.

Eager versus graph execution¶

In order to understand what torch.jit brings to the table, it’s necessary to first understand the difference between the two dominant models of execution in deep learning: eager and graph.

A deep learning framework is said to use eager execution (or eager evaluation) if it builds its computational graph (the set of steps needed to perform forward or backwards propagation through the network) at runtime. PyTorch is the classic example of a framework which is eagerly evaluated. Every forward pass through a PyTorch model constructs an autograd computational graph; the subsequent call to backwards then consumes (and destroys!) this graph (for more on PyTorch autograd, see here).

Constructing and deconstructing objects in this way paves the way to a good developer experience. The code that’s actually executing the mathematical operations involved is ultimately a C++ or CUDA kernel, but the result of each individual operation is immediately transferred to (and accessible from) the Python process, because the Python process is the “intelligent” part—it’s what’s managing the computational graph as a whole. This is why debugging in PyTorch is as simple as dropping import pdb; pdb.set_trace() in the middle of your code.

Alternatively, one may make use of graph execution. Graph execution pushes the management of the computational graph down to the kernel level (e.g. to a C++ process) by adding an additional compilation step to the process. The state is not surfaced back to the Python process until after execution is complete.

Graph execution is faster than eager execution: the computational graph need only be built once, and the compiler can automatically find and apply optimizations to the code that aren’t possible in an interpreted context (compare the performance of Python with C, for example). However, this comes at the cost of developer experience. All of the interesting state is now managed by a C++ kernel. Debugging with pdb is no longer possible (you’ll need to attach gdb to the C++ process—not only is this a lot more work, but it also requires knowing a second programming language). Error messages are now bubbled-up C++ error messages, which tend to be opaque and hard to connect to their Python source.

When PyTorch got its start back in 2016, it wasn’t immediately obvious which execution mode was better. Today eager execution has emerged as the clear winner. PyTorch’s rapid growth in market share at the expense of TensorFlow is largely credited to its ease-of-use, which in turn is largely credited to its use of the eager execution model. TensorFlow, which used graph execution by default in version 1, switched to using eager execution by default in TensorFlow 2.

That being said, graph execution still has its uses. In production settings, any gain in performance can produce significant reductions in the overall cost of running a model. And the pure C++ computational graphs graph execution produces are much more portable than Python computational graph. This is particularly important on embedded and mobile platforms, which offer only extremely limited Python support.

For this reason, there has been some amount of co-evolution. TensorFlow, which started as a graph framework, now supports eager. And PyTorch, which started as an eager framework, now supports graph—pytorch.jit, the subject of this post.

Here JIT stands for just-in-time compilation. In the next two sections, we’ll cover how it can be used. And in the section after that, we’ll cover why you should use it, looking at a benchmark showing how much of a performance torch.jit can create.

Using PyTorch JIT in scripting mode¶

JIT can be applied to PyTorch code in one of two ways. In this section, we’ll cover the first of these options, scripting. In the next, we’ll cover option two, tracing.

To enable scripting, use the jit.ScriptModule class and the @torch.jit.script_method decorator. This straightforwardly turns the wrapped module into a (compiler-supported) TorchScript function:

import torch.jit as jit

class MyModule(jit.ScriptModule):

def __init__():

super().__init__()

# [...]

@jit.script_method

def forward(self, x):

# [...]

pass

After running this code, and instantiating this class, MyModule is a JIT-ed (compiled) module. The module is still a Python object, but almost all of its code execution now happens in C++.

TorchScript is a subset of Python that PyTorch knows how to dynamically inspect and transform into kernel code at runtime. The syntax is exactly the same as writing Python code, but uses wrappers from the torch.jit submodule to declare that the code should be JIT-ed. The TorchScript language reference describes the allowed subset of Python.

The aim of the TorchScript project is to provide a restricted subset of Python which satisfies the properties that it is (1) useful for neural network programming and (2) easy to compile. The reference is the authoritative guide, but in general, this means things that are deterministic and side-effect free. To give a concrete example, looping over an (immutable) range or a tuple is allowed, but looping over a (mutable) list is not:

# allowed

for n in range(0, 5):

print(n)

# allowed

for n in (0, 1, 2, 3, 4):

print(n)

# not allowed (raises compile error)

ns = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for n in ns:

print(n)

a.pop()

The third code sample here demonstrates why looping over a list is forbidden: it mutates (a side effect) whilst simultaneously iterating over its elements. The compiler cannot unroll this loop—so it forbids it entirely.

In my experience, most PyTorch module code can be converted to TorchScript with not too much effort, assuming the person doing so is familiar with the codebase already. On the other hand, converting nontrivially complex code written by a different author tends to be quite hard.

Using PyTorch JIT in trace mode¶

Option two is to use tracing (torch.jit.trace for functions, torch.jit.trace_module for modules).

Tracing has you run the code on some example inputs. PyTorch directly observes the execution in order to create a matching computational graph. Importantly, the code being traced does not need to be TorchScript-compatible; it can be arbitrary Python. Essentially PyTorch is automating the process of transforming lines of Python code into lines of TorchScript code for you:

# torch.jit.trace for functions

import torch

def foo(x, y):

return 2 * x + y

traced_foo = torch.jit.trace(foo, (torch.rand(3), torch.rand(3)))

# torch.jit.trace for modules

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class Net(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.conv = nn.Conv2d(1, 1, 3)

def forward(self, x):

return self.conv(x)

n = Net()

example_weight = torch.rand(1, 1, 3, 3)

example_forward_input = torch.rand(1, 1, 3, 3)

traced_module = torch.jit.trace(n, example_forward_input)

After running this code, traced_foo and traced_module are JIT-ed (compiled) code objects that run almost completely in C++.

Tracing has two limitations.

One, tracing will destroy any control flow. Specifically, (1) any if-else in the module will only be evaluated on one code path, the code path that the same being traced passed through; and (2) for or while loops will be unrolled to a fixed-length sequence of operations. Note that PyTorch does offer an @torch.jit.unused decorator that you can use to work around this problem (by excluding it from tracing; control flow isn’t typically a performance bottleneck anyway).

Two, operations that evaluate differently based on whether the model is in train or eval mode will only execute in whatever mode the model was in at trace time. If you need to use modules that have such behavior (like Dropout or BatchNorm2d) or want to implement your own, the scripting approach—which doesn’t have this limitation—is the way to go.

The payoff—make custom layers go fast¶

The PyTorch JIT features can be used to make custom modules in your model more performant.

High-performance machine learning models built to perform at or near SOTA on a given task will almost always contain at least a few custom modules taken from current research. For example, if you are running an image-to-image segmentation model, you may be interested in embedding recently published techniques like SPADE into your model architecture.

Since such specialized layers do not yet (and may never) have implementations built directly into the PyTorch library itself, using them in your model will require implementing them yourself. However, hand-implemented neural network modules are always slower than comparable modules taken from the PyTorch standard library, because they will be missing the many low-level optimizations that PyTorch has implemented over the years.

To demonstrate, consider the following handwritten Conv2d layer, implemented using vanilla PyTorch (derived from this implementation, with some improvements). You wouldn’t write such a layer in practice of course—you’d just use torch.nn.Conv2d instead. Nevertheless, it’s a good demonstration because it’s a nontrivial layer type that most machine learning practitioners understand quite well, making it’s a good stand-in for whatever you might be implementing yourself:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class Conv2d(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self, n_channels, out_channels, kernel_size, dilation=1, padding=0, stride=1

):

super().__init__()

self.kernel_size = kernel_size

self.kernel_size_number = kernel_size * kernel_size

self.out_channels = out_channels

self.padding = padding

self.dilation = dilation

self.stride = stride

self.n_channels = n_channels

self.weights = nn.Parameter(

torch.Tensor(self.out_channels, self.n_channels, self.kernel_size**2)

)

def __repr__(self):

return (

f"Conv2d(n_channels={self.n_channels}, out_channels={self.out_channels}, "

f"kernel_size={self.kernel_size})"

)

def forward(self, x):

width = self.calculate_new_width(x)

height = self.calculate_new_height(x)

windows = self.calculate_windows(x)

result = torch.zeros(

[x.shape[0] * self.out_channels, width, height],

dtype=torch.float32, device=x.device

)

for channel in range(x.shape[1]):

for i_conv_n in range(self.out_channels):

xx = torch.matmul(windows[channel], self.weights[i_conv_n][channel])

xx = xx.view((-1, width, height))

xx_stride = slice(i_conv_n * xx.shape[0], (i_conv_n + 1) * xx.shape[0])

result[xx_stride] += xx

result = result.view((x.shape[0], self.out_channels, width, height))

return result

def calculate_windows(self, x):

windows = F.unfold(

x,

kernel_size=(self.kernel_size, self.kernel_size),

padding=(self.padding, self.padding),

dilation=(self.dilation, self.dilation),

stride=(self.stride, self.stride)

)

windows = (windows

.transpose(1, 2)

.contiguous().view((-1, x.shape[1], int(self.kernel_size**2)))

.transpose(0, 1)

)

return windows

def calculate_new_width(self, x):

return (

(x.shape[2] + 2 * self.padding - self.dilation * (self.kernel_size - 1) - 1)

// self.stride

) + 1

def calculate_new_height(self, x):

return (

(x.shape[3] + 2 * self.padding - self.dilation * (self.kernel_size - 1) - 1)

// self.stride

) + 1

To test the performance of this module, I ran the following code:

x = torch.randint(0, 255, (1, 3, 512, 512), device='cuda') / 255

conv = Conv2d(3, 16, 3)

conv.cuda()

%%time

out = conv(x)

out.mean().backward()

This module, as written, takes 35.5 ms to execute on this input.

Let’s now JIT this code (e.g. convert it to the graph runtime). To do so, I need only make a couple of changes. First, the class now needs to inherit from jit.ScriptModule, not nn.Module:

# old

class Conv2d(nn.Module):

# [...]

# new

class Conv2d(jit.ScriptModule):

# [...]

Second, I set the @jit.script_method wrapper on the forward method definition within the module code:

# old

def forward(self, x):

# [...]

@jit.script_method

def forward(self, x):

# [...]

You can see both versions of this code on GitHub.

You can, in theory, JIT the other helper functions (calculate_windows, calculate_new_width, calculate_new_height) as well, but these functions perform relatively simple math and are only called once, so I don’t think they significantly affect overall performance. The main line of code we’re trying to optimize is the core matrix multiply, torch.matmul, on line 40.

I run the same exact test code on this new, JIT-ed version of Conv2d:

x = torch.randint(0, 255, (1, 3, 512, 512), device='cuda') / 255

conv = Conv2d(3, 16, 3)

conv.cuda()

%%time

out = conv(x)

out.mean().backward()

Recall that the vanilla module took 35.5 ms to execute. The JIT version of this module executes in 17.4 ms.

By just changing two lines of code, we’ve got a 2x speedup!

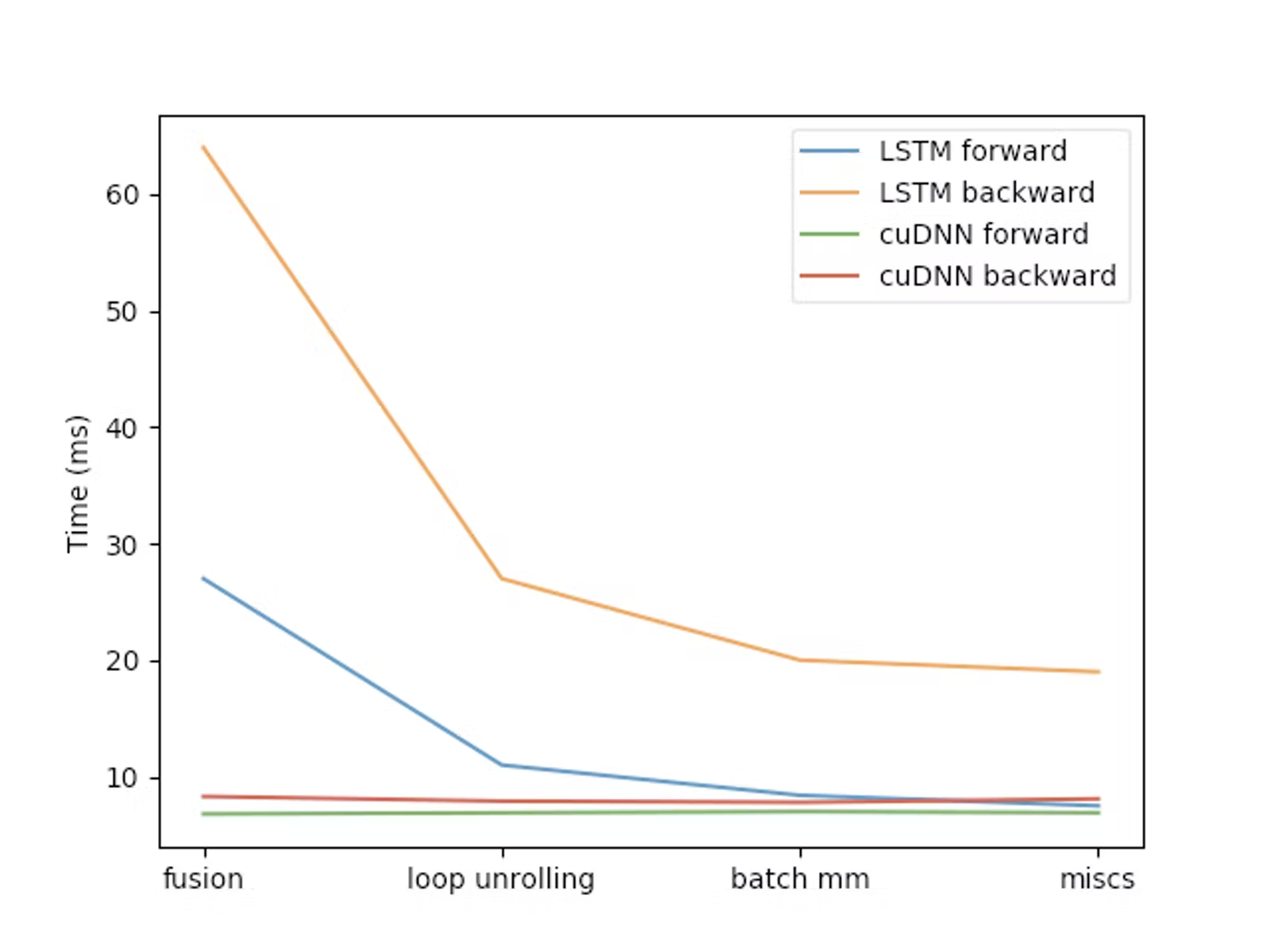

Need you any further convincing, yet more evidence of the kind of speedups that JIT enables is presented in the blog post announcing the release of the JIT feature. In that post, the PyTorch team implement a handwritten LSTM module, and benchmark the performance of this layer after a variety of JIT optimizations—operator fusion and loop unrolling being the two biggest effects:

In this case, we see order-of 3x improvement in module performance! Forward propagation in particular is as performant as it is in cuDNN (the CUDA framework you’d be using if you hated yourself and wanted to write raw CUDA code).

How is this possible? Briefly, operator fusion combines compatible sequences of mathematical operations within the module definition into a single long-running operation, allowing the C++ process to operate on the tensor without having to create an intermediate state that, were we evaluating eagerly, would have to then be resurfaced to the Python process. Loop unrolling is an extremely common compiler optimization that turns for and while loops into numbered component blocks, which the execution engine can then trivially parallelize.

Layers built into the PyTorch library (torch.nn and elsewhere) already use these optimizations and others like it everywhere they can. By using torch.jit, you can extend these compiler optimizations to your custom modules as well!

Conclusion¶

In this post we saw, at a very high level, what torch.jit is and how it can be used to greatly improve the performance of your custom module code. We saw a benchmark application to a Conv2d layer showing an approximately 2x speedup and another benchmark application to an LSTM module showing an approximately 3x speedup.

I should note that, though they are the focus of this blog post, high-performance custom modules are not the only thing that JIT allows.

PyTorch JIT also has the major benefit that it creates a C++ computational graph consumable using libtorch, PyTorch’s C++ implementation. This provides portability. Mobile and embedded platforms are usually a poor choice for Python code; meanwhile, a C++ neural network module can be consumed from any programming language capable of linking to a C++ executable, which is pretty much all of them. To this effect, the PyTorch website has recipes for Android and iOS showing how this is done.

However, this application is outside of the scope of this book!